/ 8:00 AM /

The funeral of the wife of the late Khmer Rouge leader, Pol Pot, has taken place in north-western Cambodia.

Several former senior Khmer Rouge figures were among the mourners - including former Prime Minister Khieu Samphan, ex-Foreign Minister Ieng Sary and Pol Pot's deputy, Nuon Chea.

Khieu Ponnary was cremated in a Buddhist ceremony, with hundreds of chanting monks and the very religious rituals that the ultra-communist Khmer Rouge had tried to eradicate.

As Pol Pot's first wife, Khieu Ponnary was regarded by genocide investigators as a key witness to the activities of the brutal Khmer Rouge administration in the 1970s.

Her death, on Wednesday at the age of 83, comes just months after the United Nations and Cambodia signed a long-awaited agreement to put surviving members of the regime on trial for genocide.

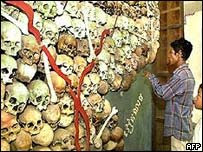

The Khmer Rouge has been blamed for the deaths of more than a million people, through execution, starvation and hard labour.

Human rights groups said Khieu Ponnary's death highlighted the need to prosecute former Khmer Rouge members before they died of natural causes.

So far, no senior figures have been charged for the genocide, and Pol Pot himself died in 1998 without having faced any such inquiry.

Ieng Sary, who looked frail and old at the funeral, is typical of many of the surviving Khmer Rouge leaders in that he lives freely under a government amnesty.

Mental illness

Known as "Sister Number One", Khieu Ponnary played a key role in the development of the Khmer Rouge in the 1950s and 1960s, and was head of the Cambodian national women's association during the period 1975-1979.

She struggled with mental illness from the mid-1970s, but eventually succumbed to cancer and old age, according to her nephew Ieng Vuth.

Khieu Ponnary was the first Cambodian woman to graduate from high school.

She then went to Paris to continue her education, and it was there that she met Pol Pot, also known as Saloth Sar, in 1951.

They married in 1956 and returned to Cambodia, where she helped him build his revolutionary ultra-communist movement, the Khmer Rouge.

Although she was introduced to a cheering crowd as the "mother of the revolution" in 1978, it is thought that her dementia had got the better of her by the mid-1970s, and soon after is reported to have spent time at a mental institution in Beijing.

Her mental state meant that she was never really a serious candidate for the genocide tribunal, according to Cambodian academic Craig Etcheson.

"It is unlikely that she held any position of responsibility in the Khmer Rouge regime, which might potentially have rendered her liable to indictment under the mandate of the proposed tribunal," Mr Etcheson told the French news agency AFP.